The A to Z of Creative Writing Methods is an alphabetical collection of essays to prompt consideration of method within creative writing research and practice.

Almost sixty contributors from a range of writing traditions and across multiple forms and genre are represented in this volume: from poets, essayists, novelists and performance writers, to graphic novelists, illustrators, and those engaged in multi-media writing or writing-related arts activism. Contributors bring to this collection their distinct and diverse literary and cultural contexts, defining, expanding and enacting the methods they describe, and providing new possibilities for creative writing practice.

Featuring Tina’s 2020 chapter, ‘Permission’.

‘Indigenous Literary Studies in Aotearoa New Zealand’ @ oxford research encyclopedias (2020)

Indigenous literary studies in Aotearoa New Zealand are characterized primarily by tension between abundance and scarcity. The abundance relates to a wealth of writers, texts, and forms, both contemporary and archival. Many historical texts and literary contexts are being revealed and investigated for the first time. Abundance in this context also signifies the richness of approach, technique, and language use in both contemporary and archival texts. The significance of this deep archive is yet to be fully realized, due in part to the scarcity of scholars in Indigenous literatures of Aotearoa, a lack which is cemented and institutionalized by the absence of university courses that focus primarily on Indigenous literatures in English. A paucity of published Māori and Pasifika creative texts, particularly long-form fiction, further solidifies a perceptible absence in New Zealand writing. Significant scholarship is being developed despite this, however. And rather than being limited to viewing Indigenous literatures through the lens of English or New Zealand literary history, Indigenous scholars present innovative historical, geographical, and creative genre frameworks that open up multiple ways of reading and engaging with Indigenous literatures.

Meeting the Ancestor on the Road: From the room in which I write and sleep, I can see Mount Taranaki, if he is showing himself, for he often wears a hat of clouds, and sometimes cloaks himself entirely so that you wouldn’t know he was there if you didn’t already know he’s there. Taranaki is a stunning volcanic mountain whose form undeniably dominates the skyline when he allows it, cone-shaped, snowy at the peak, surrounded by fertile volcanic soils in a wide circle that extends to the ocean. Looking at a topographical map, you can imagine the eruption, just as we do as we climb over metres of large black boulders to get to the sea. Last night we ate in his company, taking our chairs outside since he was showing his face so clearly, and it was a friendly, peaceful time with him. It was the 5th of November, a date which is significant to Taranaki and his people, of which I am one…

Maori Writing: Speaking with Two Mouths (2018)

My taonga has a single eye and two mouths. The two mouths face in separate directions. On first seeing it I knew that this taonga representedthe task of the writer, particularly the Māori writer: to speak with two mouths at once;to communicate between two sometimes opposing forces;to exist at the centre of the paradox. In particular, this taonga spoke to me as a mixed Māori-Pākehā individualtelling the particular stories I tell, and as a Māori person writing in English. There is a duality in the fact of this act for Māori; writing in English is already an act of translation. But there is also added complexity in the modernity of the Indigenous writer. We are not performing simple translationsinto Englishof traditional ways of being or of pristine cultures. Ifwe try to describe our cultures that way we end up solidifying something that was never solid. Our cultures, like any cultures, are in constant flux, so from the very first contact between Māori tribes and European settlers, our cultures transformed.

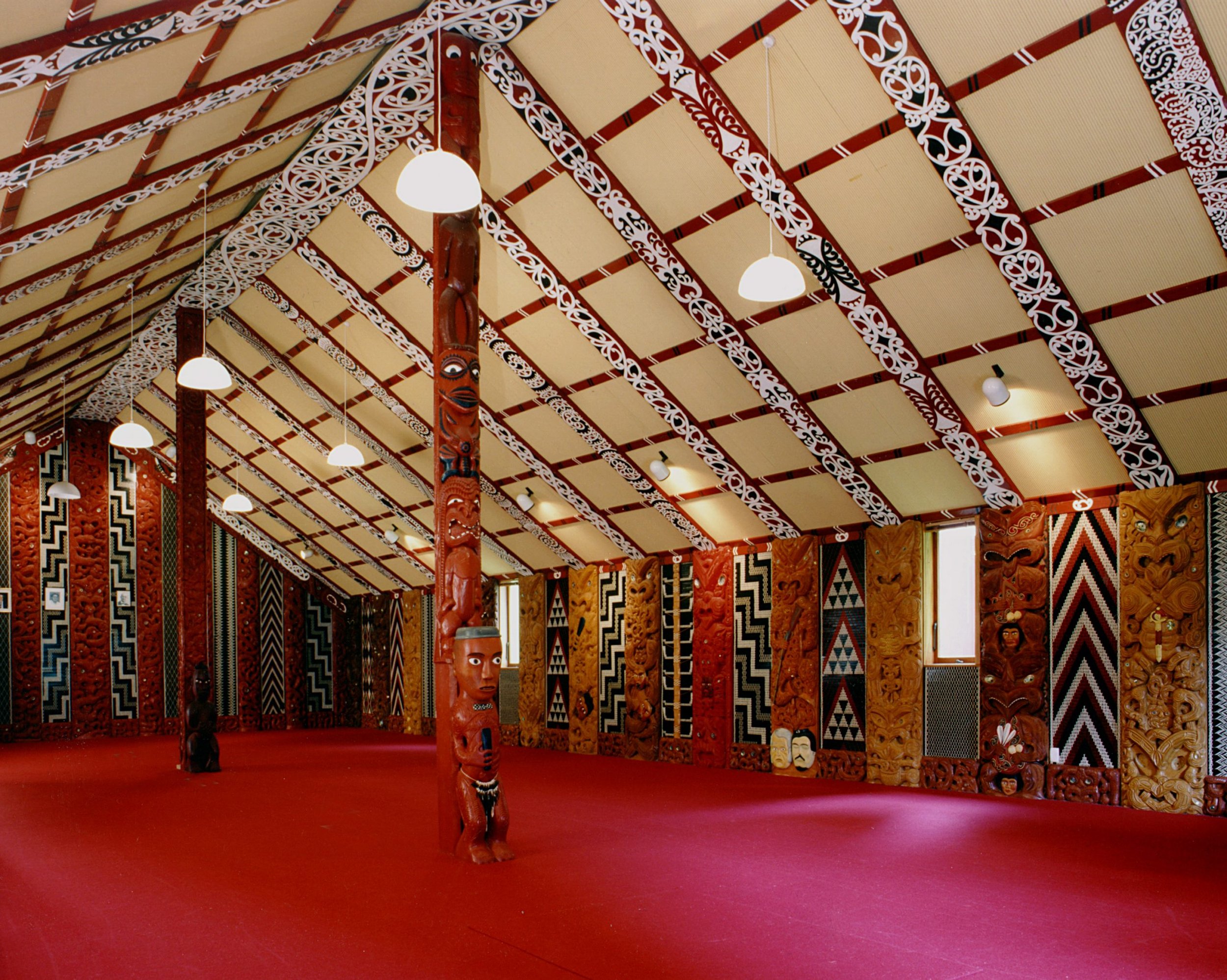

Wharenui interior, Te Herenga Waka Marae

The Whakapapa of Our Literature

Instead of placing Māori and Pacific literatures as late arrivals to English literature, we will instead recognise a whakapapa of Māori literature that goes all the way back to Te Moana nui a Kiwa.

This reconnection to our Oceanic whakapapa acknowledges relationships with other Pacific nations that existed long before European exploration of the Pacific. Following Epeli Hau’ofa and subsequent Pacific scholars, we situate ourselves in the Pacific as an ocean continent.

The Latin alphabet, reading and writing, books, and English literature were late but very welcome additions to this cultural landscape. We already had our stories and poems and other forms of literature, but we were very happy to incorporate new ways of transmitting thought. So the European contribution to our literature was important. But from this vantage point, English is the latecomer.

Black Marks on the White Page launch, 2018

Bleeding on the Page: On writing, community and reviews (2020)

But there are things about the writing world that are much harder to talk about or even describe. Tensions that are likely apparent inside writing lives and communities but not so much outside of them. This year, watching my students take their first tentative steps into writing lives, I became aware not of how things are becoming more open and accepting, but of how the writing world might be in danger of somehow contracting. Sometimes, when a movement is growing, and our literature certainly is, being more colourful and multi-faceted now than it’s ever been before, a certain fear creeps in. Sometimes people deal with this by trying to make hard and fast rules about how things are done and what is allowed to be said. It’s a weird paradox that our efforts to open up our literature can produce a new sort of orthodoxy. As we prise apart older systems and canonical forms, the force of so many tensions pulling against each other can be scary.

Matahi Whakataka-Brightwell’s carved Ngāti Tūwharetoa tipuna, Ngatoroirangi, Lake Taupō.

Stories can Save Your Life (2017)

Our [literary] whare is… a kaupapa whare. It’s a whare that must welcome and absorb and connect all the literatures and writers and readers of Aotearoa. It is a whare for all of us.

Imagine it. The swirling, spiralling, notched lines of poetry; the strong limbs and bright eyes of fiction; various non-fictions in repeating patterns overhead. Imagine the sumptuous kōrero that takes place in this whare late into the night, the breaking away for Aotearoa’s most delicious kai, shipped in from all regions, the coming together for waiata of the most melodious varieties, the drums of the Pacific like heartbeats behind our songs.

Imagine the laughter.

Imagine the tears.

And, oh, metaphors to make your knees weak.